TEHRAN

TEHRAN HISTORY

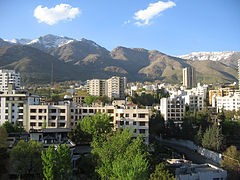

Tehran (Persian: تهران Tehrān, pronounced [tehˈrɒːn] ( listen)) is the capital of Iran and Tehran Province. With a population of around 8.8 million in the city and 15 million in its larger metropolitan area, Tehran is the most populous city in Iran and Western Asia,[4] and it has the second-largest metropolitan area in the Middle East. It is ranked 29th in the world by the population of its metropolitan area.[5]

In the Classical era, part of the territory of present-day Tehran was occupied by Rhages, a prominent Median city.[6] It was subject to destruction following the Arab, Turkic, and Mongol invasions. Its modern-day inheritor remains as an urban area absorbed into the metropolitan area of Greater Tehran.

Tehran was first chosen as the capital of Iran by Agha Mohammad Khan of the Qajar dynasty in 1796, in order to remain within close reach of Iran’s territories in the Caucasus, before being separated from Iran as a result of the Russo-Iranian Wars, and to avoid the vying factions of the previously ruling Iranian dynasties. The capital has been moved several times throughout the history, and Tehran is the 32nd national capital of Iran.

The city was the seat of the Qajars and Pahlavis, the two last monarchies of Iran. It is home to many historical collections, including the royal complexes of Golestan, Sa’dabad, and Niavaran, as well as the country’s most important governmental buildings of the modern era.

Large scale demolition and rebuilding began in the 1920s, and Tehran has been a destination for the mass migrations from all over Iran since the 20th century.[7]

Tehran’s most famous landmarks include the Azadi Tower, a memorial built under the reign of the Pahlavi dynasty, and the Milad Tower, the world’s sixth-tallest self-supporting tower which was completed in 2007. The Tabiat Bridge, a newly-built landmark, was completed in 2014.[8]

The majority of the population of Tehran are Persian-speaking people,[9][10] and roughly 99% of the population understand and speak Persian, but there are large populations of other Iranian ethnicities such as Azerbaijanis, Armenians, Lurs, and Kurds who live in Tehran and speak Persian as their second language.[11]

Tehran is served by the international airports of Mehrabad and Khomeini, a central railway station, the rapid transit system of Tehran Metro, a bus rapid transit system, trolleybuses, and a large network of highways.

There have been plans to relocate Iran’s capital from Tehran to another area, due mainly to air pollution and the city’s exposure to earthquakes. To date, no definitive plans have been approved. A 2016 survey of 230 cities by consultant Mercer ranked Tehran 203rd for quality of life. According to the Global Destinations Cities Index in 2016, Tehran is among the top ten fastest growing destinations.

History

The origin of the name Tehran is uncertain. The settlement of Tehran dates back over 7,000 years.

Classical era

Tehran is situated within the historical region of Media (Old Persian: Māda) in northwestern Iran. By the time of the Median Empire, a part of the territory of present-day Tehran was a suburb of the prominent Median city of Rhages (Old Persian: Ragā). In the Avesta’s Videvdat (i, 15), Rhages is mentioned as the 12th sacred place created by Ohrmazd. In Old Persian inscriptions, Rhages appears as a province (Bistun 2, 10–18). From Rhages, Darius I sent reinforcements to his father Hystaspes, who was putting down the rebellion in Parthia (Bistun 3, 1–10).[16] In some Middle Persian texts, Rhages is given as the birthplace of Zoroaster, although modern historians generally place the birth of Zoroaster in Khorasan. Rhages’s modern-day inheritor, Ray, is a city located towards the southern end of Tehran, which has been absorbed into the metropolitan area of Greater Tehran.

Mount Damavand, the highest peak of Iran, which is located near Tehran, is an important location in Ferdowsi’s Šāhnāme,[18] the Iranian epic poem that is based on the ancient legends of Iran. It appears in the epics as the homeland of the protoplast Keyumars, the birthplace of king Manuchehr, the place where king Freydun binds the dragon fiend Aždahāk (Bivarasp), and the place where Arash shot his arrow from.[18]

Medieval period

During the reign of the Sassanian Empire, in 641, Yazdgerd III issued his last appeal to the nation from Rhages, before fleeing to Khorasan.[16] Rhages was dominated by the Parthian Mehran family, and Siyavakhsh—the son of Mehran the son of Bahram Chobin—who resisted the 7th-century Muslim invasion of Iran.[16] Because of this resistance, when the Arabs captured Rhages, they ordered the town to be destroyed and rebuilt anew by traitor aristocrat Farrukhzad.[16]

In the 9th century, Tehran was a well known village, but less known than the city of Rhages, which was flourishing nearby. Rhages was described in detail by 10th-century Muslim geographers.[16] Despite the interest that Arabian Baghdad displayed in Rhages, the number of Arabs in the city remained insignificant and the population mainly consisted of Iranian of all classes.[16][19]

The Oghuz Turks invaded Rhages discretely in 1035 and 1042, but the city was recovered under the reigns of the Seljuks and the Khwarezmians.[16] Medieval writer Najm od Din Razi declared the population of Rhages about 500,000 before the Mongol invasion. In the 13th century, the Mongols invaded Rhages, laid the city in ruins, and massacred many of its inhabitants.[16] Following the invasion, many of the city’s inhabitants escaped to Tehran.

In July 1404, Castilian ambassador Ruy González de Clavijo visited Tehran while on a journey to Samarkand, the capital of Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur, who ruled Iran at the time. In his diary, Tehran was described as an unwalled region.

Early modern era

Italian traveler Pietro della Valle passed through Tehran overnight in 1618, and in his memoirs, he mentioned the city as Taheran. English traveler Thomas Herbert entered Tehran in 1627, and mentioned it as Tyroan. Herbert stated that the city had about 3,000 houses.

In the early 18th century, Karim Khan of the Zand dynasty ordered a palace and a government office to be built in Tehran, possibly to declare the city his capital; but he later moved his government to Shiraz. Eventually, Qajar king Agha Mohammad Khan chose Tehran as the capital of Iran in 1776.

Agha Mohammad Khan’s choice of his capital was based on a similar concern for the control of both northern and southern Iran. He was aware of the loyalties of the inhabitants of former capitals Isfahan and Shiraz to the Safavid and Zand dynasties respectively, and was wary of the power of the local notables in these cities. Thus, he probably viewed Tehran’s lack of a substantial urban structure as a blessing, because it minimized the chances of resistance to his rule by the notables and by the general public. Moreover, he had to remain within close reach of Azerbaijan and Iran’s integral northern and southern Caucasian territories—at that time not yet irrevocably lost per the treaties of Golestan and Turkmenchay to the neighboring Russian Empire—which would follow in the course of the 19th century.

Tehran in 1857.

After 50 years of Qajar rule, the city still barely had more than 80,000 inhabitants. Up until the 1870s, Tehran consisted of a walled citadel, a roofed bazaar, and the three main neighborhoods of Udlajan, Chale-Meydan, and Sangelaj, where the majority resided.

The first development plan of Tehran in 1855 emphasized the traditional spatial structure. Architecture, however, found an eclectic expression to reflect the new lifestyle. The second major planning exercise in Tehran took place under the supervision of Dar ol Fonun. The 1878 plan of Tehran included new city walls, in the form of a perfect octagon with an area of 19 square kilometers, which mimicked the Renaissance cities of Europe.

Late modern era

The growing social awareness of civil rights resulted in the Constitutional Revolution and the first constitution of Iran in 1906. On June 2, 1907, the parliament passed a law on local governance known as the Baladie (municipal law), providing a detailed outline on issues such as the role of councils within the city, the members’ qualifications, the election process, and the requirements to be entitled to vote. The then Qajar monarch Mohammad Ali Shah abolished the constitution and bombarded the parliament with the help of the Russian-controlled Cossack Brigade on June 23, 1908. That followed the capture of the city by the revolutionary forces of Ali-Qoli Khan (Sardar Asad II) and Mohammad Vali Khan (Sepahsalar e Tonekaboni) on July 13, 1909. As a result, the monarch was exiled and replaced with his son Ahmad, and the parliament was re-established.

After World War I, the constituent assembly elected Reza Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty as the new monarch, who immediately suspended the Baladie law of 1907, replacing the decentralized and autonomous city councils with centralist approaches of governance and planning.[23]

From the 1920s to the 1930s, under the rule of Reza Shah, the city was essentially rebuilt from scratch. That followed a systematic demolition of several old buildings, including parts of the Golestan Palace, Tekye Dowlat, and Tupkhane Square, which were replaced with modern buildings influenced by classical Iranian architecture, particularly the building of the National Bank, the Police Headquarters, the Telegraph Office, and the Military Academy.

The changes in urban fabric started with the street-widening act of 1933, which served as a framework for changes in all other cities. The Grand Bazaar was divided in half and many historic buildings were demolished to be replaced with wide straight avenues.[24] As a result, the traditional texture of the city was replaced with intersecting cruciform streets that created large roundabouts, located on major public spaces such as the bazaar.

As an attempt to create a network for easy transportation within the city, the old citadel and city walls were demolished in 1937, replaced by wide streets cutting through the urban fabric. The new city map of Tehran in 1937 was heavily influenced by modernist planning patterns of zoning and gridiron networks.[23]

During World War II, Soviet and British troops entered the city. In 1943, Tehran was the site of the Tehran Conference, attended by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

The establishment of the planning organization of Iran in 1948 resulted in the first socio-economic development plan to cover from 1949 to 1955. These plans not only failed to slow the unbalanced growth of Tehran, but with the 1962 land reforms that Reza Shah’s son and successor Mohammad Reza Shah named the White Revolution, Tehran’s chaotic growth was further accentuated.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Tehran was rapidly developing under the reign of Mohammad Reza Shah. Modern buildings altered the face of Tehran and ambitious projects were envisioned for the following decades. In order to resolve the problem of social exclusion, the first comprehensive plan of Tehran was approved in 1968. The consortium of Iranian architect Abd-ol-Aziz Farmanfarmaian and the American firm of Victor Gruen Associates identified the main problems blighting the city to be high density suburbs, air and water pollution, inefficient infrastructure, unemployment, and rural-urban migration. Eventually, the whole plan was marginalized by the 1979 Revolution and the subsequent Iran–Iraq War.[23]

Tehran’s most famous landmark, the Azadi Tower, was built by the order of the Shah in 1971. It was designed by Hossein Amanat, an architect who won a competition to design the monument, combining elements of classical Sassanian architecture with post-classical Iranian architecture. Formerly known as the Shahyad Tower, it was built in commemoration of the 2,500th year of the foundation of the Imperial State of Iran.

During the 1980–1988 Iran–Iraq War, Tehran was the target of repeated Scud missile attacks and air strikes.

The 435-meter-high Milad Tower, which was part of the proposed development projects in pre-revolutionary Iran,[25] was completed in 2007, and has thence become a famous landmark of Tehran. The 270-meter pedestrian overpass of Tabiat Bridge is a newly-built landmark,[8]designed by award winning architect Leila Araghian, which was completed in 2014.

Geography

Location and subdivisions

The metropolis of Tehran is divided into 22 municipal districts, each with its own administrative center. 20 of the 22 municipal districts are located in Tehran County’s Central District, while the districts 1 and 20 are respectively located in the counties of Shemiranat and Ray.

Although administratively separate, the cities of Ray and Shemiran are often considered part of Greater Tehran.

Northern Tehran is the wealthiest part of the city,[26] consisting of various districts such as Zaferanie, Jordan, Elahie, Pasdaran, Kamranie, Ajodanie, Farmanie, Darrous, Qeytarie, and Qarb Town.[27][28] While the center of the city houses government ministries and headquarters, commercial centers are more located towards further north.

Urban sustainability analysis of the metropolitan area of Tehran, using the ‘Circles of Sustainability’ method of the UN Global Compact Cities Programme.

Tehran features a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification: BSk) with continental climate characteristics and a Mediterranean climate precipitation pattern. Tehran’s climate is largely defined by its geographic location, with the towering Alborz mountains to its north and the country’s central desert to the south. It can be generally described as mild in spring and autumn, hot and dry in summer, and cold and wet in winter.

See also: List of shopping malls in Iran

Tehran has a wide range of shopping centers, and is home to over 60 modern shopping malls.[52] The city has a number of commercial districts, including those located at Valiasr, Davudie, and Zaferanie. The largest old bazaars of Tehran are the Grand Bazaar and the Bazaar of Tajrish.

Most of the international branded stores and upper-class shops are located in the northern and western parts of the city. Tehran’s retail business is growing with several newly-built malls and shopping centers.[52]

Tourism in Iran

Tehran, as one of the main tourist destinations in Iran, has a wealth of cultural attractions. It is home to royal complexes of Golestan, Saadabad and Niavaran, which were built under the reign of the country’s last two monarchies.

There are several historic, artistic and scientific museums in Tehran, including the National Museum, the Malek Museum, the Cinema Museum at Ferdows Garden, the Abgineh Museum, Museum of the Qasr Prison, the Carpet Museum, the Reverse Glass Painting Museum (vitray art), and the Safir Office Machines Museum. There is also the Museum of Contemporary Art, which hosts works of famous artists such as Van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, and Andy Warhol.

The Iranian Imperial Crown Jewels, one of the largest jewel collections in the world, are also on display at Tehran’s National Jewelry Museum.

A number of cultural and trade exhibitions take place in Tehran, which are mainly operated by the country’s International Exhibitions Company. Tehran’s annual International Book Fair is known to the international publishing world as one of the most important publishing events in Asia.[53]

A number of streets in Tehran are named after international figures, including:

• Henri Corbin Street, central Tehran.

• Simon Bolivar Boulevard, northwestern Tehran.

• Edward Browne Street, near the University of Tehran.

• Gandhi Street, northern Tehran.

• Mohammad Ali Jenah Expressway, western Tehran.

• Iqbal Lahori Street, eastern Tehran.

• Patrice Lumumba Street, western Tehran.

• Nelson Mandela Boulevard, northern Tehran.

• Bobby Sands Street, western side of the British Embassy.

Tehran’s bus rapid transit at the Azadi Terminal.

Buses have served the city since the 1920s. Tehran’s transport system includes conventional buses, trolleybuses, and bus rapid transit(BRT). The city’s four major bus stations include the South Terminal, the East Terminal, the West Terminal, and the northcentral Beyhaghi Terminal.

The trolleybus system was opened in 1992, using a fleet of 65 articulated trolleybuses built by Czechia’s Škoda.[57] This was the first trolleybus system in Iran.[57] In 2005, trolleybuses were operating on five routes, all starting at Imam Hossein Square.[58] Two routes running northeastwards operate almost entirely in a segregated busway located in the middle of the wide carriageway along Damavand Street, stopping only at purpose-built stops located about every 500 metres along the routes, effectively making these routes trolleybus-BRT (but they are not called such). The other three trolleybus routes run south and operate in mixed-traffic. Both route sections are served by limited-stop services and local (making all stops) services.[58] A 3.2-kilometer extension from Shoosh Square to Rah Ahan Square was opened in March 2010.[59]

Tehran’s bus rapid transit (BRT) was officially inaugurated in 2008. It has three lines with 60 stations in different areas of the city. As of 2011, the BRT system had a network of 100 kilometres (62 miles), transporting 1.8 million passengers on a daily basis. The city has also developed a bicycle sharing system that includes 12 hubs in one of Tehran’s districts.[60]

Railway and subway[edit]

See also: Iranian Railways and Tehran Metro

Tehran has a central railway station that connects services round the clock to various cities in the country, along with a Tehran–Europe train line also running.

The feasibility study and conceptual planning of the construction of Tehran’s subway system were started in the 1970s. The first two of the eight projected metro lines were opened in 2001.

Parks and green spaces

There are over 2,100 parks within the metropolis of Tehran,[61] with one of the oldest being Jamshidie Park, which was first established as a private garden for Qajar prince Jamshid Davallu, and was then dedicated to the last empress of Iran, Farah Pahlavi. The total green space within Tehran stretches over 12,600 hectares, covering over 20 percent of the city’s area. The Parks and Green Spaces Organization of Tehran was established in 1960, and is responsible for the protection of the urban nature present in the city.

Tehran’s Birds Garden is the largest bird park of Iran. There is also a zoo located on the Tehran–Karaj Expressway, housing over 290 species within an area of about five hectares.

There are four parks in Tehran established exclusively for women, totaling about 80 hectares in area,[61] in which the female mandatory dress codes are not required.

12 ski resorts operate in Iran, the most famous being Tochal, Dizin, and Shemshak, all within one to three hours from the city of Tehran.

Tochal’s resort is the world’s fifth highest ski resort at over 3,730 meters (12,240 feet) above sea level at its highest point. It is also the world’s nearest ski resort to a capital city. The resort was opened in 1976, shortly before the 1979 Revolution. It is equipped with a 8-kilometre-long (5 mi) gondola lift that covers a huge vertical distance.[76] There are two parallel chair ski lifts in Tochal that reach 3,900 meters (12,800 feet) high near Tochal’s peak (at 4,000 m/13,000 ft), rising higher than the gondola’s 7th station, which is higher than any of the European ski resorts. From the Tochal peak, one has a spectacular view of the Alborz range, including the 5,610-metre-high (18,406 ft) Mount Damavand, a dormant volcano.

Tehran is the site of the national stadium of Azadi, the biggest stadium by capacity in West Asia, where many of the top matches of Iran’s Premier League are held. The stadium is a part of the Azadi Sport Complex, which was originally built to host the 7th Asian Games in September 1974. This was the first time the Asian Games were hosted in West Asia. Tehran played host to 3,010 athletes from 25 countries/NOCs, which was at the time the highest number of participants since the inception of the Games.[77] That followed hosting the 6th AFC Asian Cup in June 1976, and then the first West Asian Games in November 1997. The success of the games led to the creation of the West Asian Games Federation(WAGF), and the intention of hosting the games every two years.[78] The city had also hosted the final of the 1968 AFC Asian Cup. Several FIVB Volleyball World League courses have also been hosted in Tehran

Iranian cuisine

Tehran has many modern and traditional restaurants and cafes, serving both traditional Iranian and cosmopolitan cuisine. One of the most popular dishes of the city is chelow kabab. Pizzerias, sandwich shops and kebab shops make up the majority of food outlets in the city.

Panoramic views

|

|

|

| -18(°C) | |

| Wind | (mph) |

| Pressure | (in) |

| Visibility | (mi) |

| UV Index | - |

| Humidity | (in) |